Case Studies

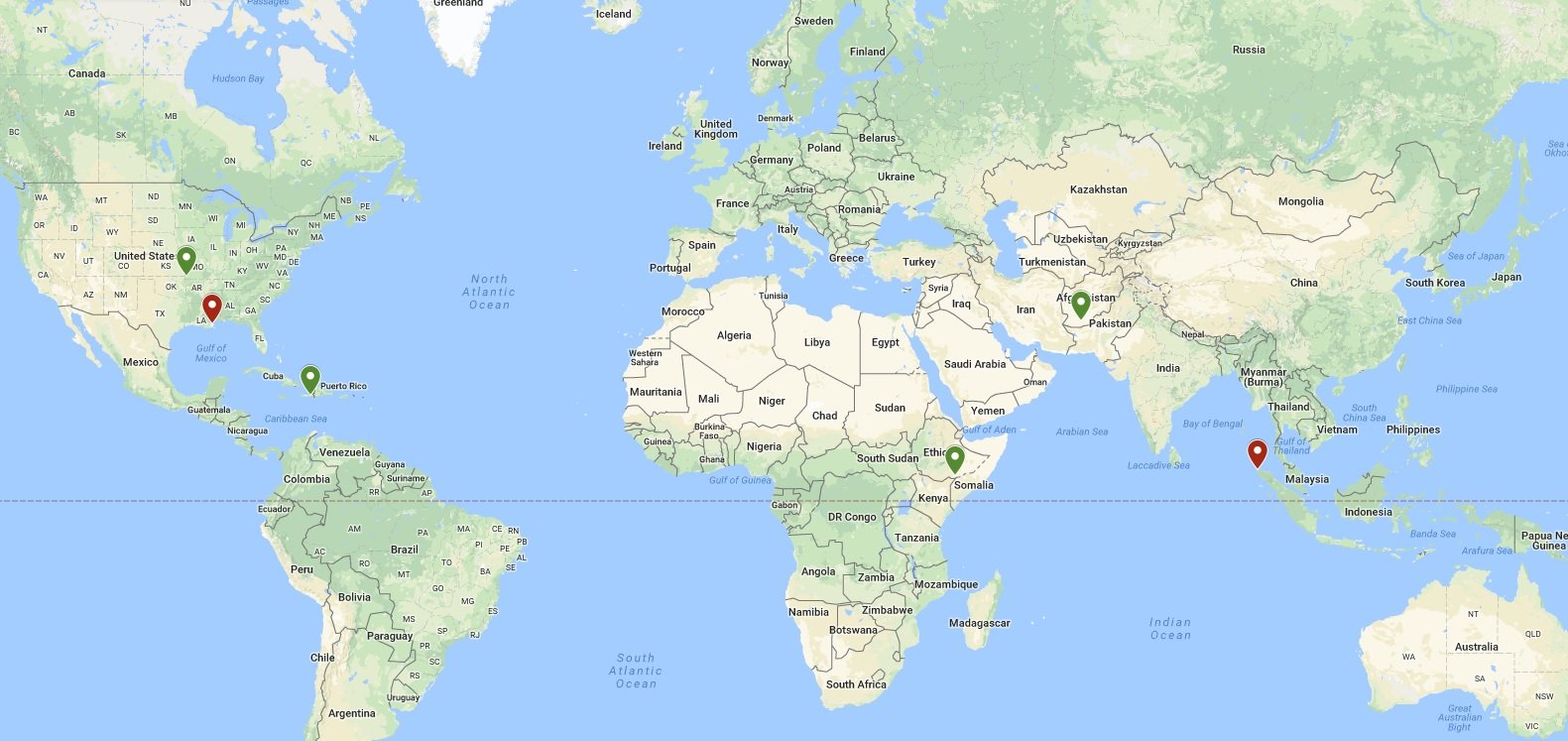

Four of the six cases below highlight qualities of success in disaster recovery and/or DRR interventions. These cases help demonstrate the common threads of success that accompany attention to local cultural values and ways of doing things. Two contrasting cases demonstrate how cultural neglect can lead to undesirable outcomes.

All the cases were taken from the direct work of CADAN members. We acknowledge that categorizing the following cases as “Successful” or “Problematic” is an over-simple evaluation to describe what went well or changed for the better. In reality, it is nuanced. The individual experiences vary widely, and responses change over time.

Successful Case Studies

Multiple Provinces, Afghanistan

Type

Drought recovery

2008

Location

Multiple provinces,

Afghanistan

“

The program made use of existing community-based decision-making structures, which were empowered to set eligibility criteria and award vouchers based on applications made by farmers.

In 2008, much of Afghanistan was trying to recover from years of drought, crop failure and lost income, as well as disruption from conflict. Farmers had no inputs left with which to plant for the coming season. Seeking to re-establish the traditionally grown wheat that more sustainably and directly addressed household food security and enabled community independence, an agricultural recovery and livelihood support program was designed with community input, and funded by the US government. Eighteen provinces in northern Afghanistan were chosen for the first phase of the program.

Cultural attitudes about work, livelihood investment, supporting a family, social and economic networks, agricultural knowledge, expertise and preferences, and personal dignity were explored with male and female farmers to shape a new approach.

Farmers were fiercely proud and self-sufficient, and indicated the local culture viewed accepting charity as shameful, but external assistance would be acceptable if a rural producer’s dignity remained intact. This insight resulted in the design of an agricultural voucher program that required a 15 percent co-pay from each beneficiary, implying ownership and retaining self-worth. The program made use of existing community-based decision-making structures, which were empowered to set eligibility criteria and award vouchers based on applications made by farmers. Local suppliers were used to redeem vouchers, supporting local markets and long-standing socio-economic networks and systems of economic relations. The vouchers allowed individual farmers to use their own decision-making and agricultural expertise to choose the precise combination of supplies they needed. Agricultural training was offered on-demand, but not mandated, for those who chose to learn improved techniques. This process gave local people the power to assess the situation, determine a course of action, and access the resources necessary to create change. The program’s success resulted in it being eventually expanded to most of Afghanistan’s provinces.

Dollo Ado, Ethiopia

Type

Water catchment

Drought, 2011

Location

Dollo Ado

Somali Region, Ethiopia

“

While the traditional technology and management were utilized, the program also introduced technology improvements that would make them more sustainable, more durable, more sufficient and efficient, more sanitary, and safer. Each birket was carefully engineered to be a size that would provide sufficient water for one community for the entire period of the 3-5 month dry season.

During 2011 the massive drought across the Horn of Africa had severely endangered lives and destroyed livelihoods. Without water, crops, animals, and people would perish. In addition to the supply of immediately needed emergency water, more sustainable solutions were needed to address ever more frequent recurrent droughts that would mitigate continually repeated emergency responses.

Research indicated that a traditional water storage technology, and social management system, had existed for communities to mitigate dry seasons and droughts in the past but it had fallen out of use and was in serious disrepair. Hand-dug reservoirs, called “birkets,” large enough for an entire small community had filled with runoff from the short rainy seasons in the area. They were built with shared community-contributed labor. During the dry season, community elders managed a household water rationing system. Over time, this system was supplanted by externally introduced much smaller plastic water tanks, that had to be filled by water tanker trucks. Communities became dependent on external, and costly, water resources, and the cycle was repeated annually.

This disaster risk reduction program rebuilt the community birkets. While the traditional technology and management were utilized, in full collaboration with the community members themselves, the program also introduced technology improvements that would make them more sustainable, more durable, more sufficient and efficient, more sanitary, and safer. Each birket was carefully engineered to be a size that would provide sufficient water for one community for the entire period of the 3-5 month dry season. They were dug by community labor, organized by village elders. To deter deterioration and extend longevity they were lined with concrete. To maximize rain runoff they were carefully sited to take advantage of ground contours, while also being put in the location and at the distance that the communities preferred. To prevent the cause of the greatest water loss, evaporation, a roof was added. The roof also prevented animals and children from falling in, animals from contaminating the water (a special animal watering area was added also), and other desert debris finding its way into the water. The community was responsible for re-establishing their own system for guarding, maintaining, and rationing the water during times of need.

Léogâne, Haiti

Type

Disaster risk reduction

Post-earthquake, 2010

Location

Léogâne

Haiti

“

To enhance ownership, increase speed of construction, and extend scarce program resources, households were asked to contribute labor to building their transitional shelters, according to their skill and capacity level. The shelters were designed to make best use of salvaged materials (along with the new building materials) and to introduce simple, low-tech, low-cost risk mitigation techniques such as roof straps and raised floors.

For this post-earthquake transitional shelter program in 2010 cultural information allowed accommodation of ideas of privacy and community, safety and proximity to social networks, preserving informal safety nets, and providing local participants a sense of ownership and dignity. Families did not want to move into settlements or camps and wanted to stay at the location of their damaged or destroyed homes. Being elsewhere would make it difficult to salvage their belongings, retain and protect rights to their property, rebuild their homes, would take them farther from accustomed livelihoods and resources, and would remove them from proximity to friends, neighbors and family that formed part of their coping systems. Therefore the transitional shelters, funded by a US government grant, were built beside their former homes. Also, research shows that when shelters are built on preferred locations, they very often become the core for extending them into permanent housing, facilitating the process of recovery. To enhance ownership, increase speed of construction, and extend scarce program resources, households were asked to contribute labor to building their transitional shelters, according to their skill and capacity level. The shelters were designed to make best use of salvaged materials (along with the new building materials) and to introduce simple, low-tech, low-cost risk mitigation techniques such as roof straps and raised floors. Written and pictorial instructions were developed and trained builders were readily available to provide advice, guidance, and building assistance, as needed, and tools were provided for sets of households to share.

Joplin, Missouri

Type

Recovery

Post-tornado, 2011

Location

Joplin, Missouri

USA

“

For the almost entirely middle-class nuclear families in the affected areas of the city, their recovery process used language and organizing activities that aligned fairly smoothly with outside organizations’ existing templates for reconstruction and support.

Joplin is heralded as a model of successful recovery following the 2011 tornado that killed 161 people and damaged or destroyed over 8,000 structures, a third of the city’s built environment. The process of recovery benefited enormously from survivor narratives and community organization that were readily identifiable and relatable. For the almost entirely middle-class nuclear families in the affected areas of the city, their recovery process used language and organizing activities that aligned fairly smoothly with outside organizations’ existing templates for reconstruction and support. These commonalities were cultural. Highlighting the specificity of Joplin’s success is neighboring Duquesne. The town’s more economically diverse population shared the same tornado devastation and recovery programs, but not the same smooth recovery outcomes.

Banda Aceh, Indonesia

Type

Early/Initial Housing Recovery

Post-Indian Ocean Tsunami, 2005

Location

Banda Aceh Region fishing villages

Indonesia

“

Initially, little local consultation occurred regarding the tsunami victims’ preferences or cultural styles of habitation organization.

When the earthquake and tsunami hit nations in the Indian Ocean in 2004, more than 230,000 lives were lost. In total, the tsunami displaced more than two million people in Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Thailand and India, and completely devastated more than half a million houses.

In the Banda Aceh Region, against the total devastation of entire fishing villages, the international emergency response was massive. Numerous aid organizations hastily tried to rebuild local housing as fast as possible, at tremendous overall cost, in order to enable households to return to their lives and livelihoods. But without international, governmental, or inter-organizational coordination or agreement on building and design standards at the outset, the result was a mosaic of very different shelter designs, styles, and inconsistent quality, built almost entirely according to aid agencies' own plans and ideas about local housing. Initially, little local consultation occurred regarding the tsunami victims’ preferences or cultural styles of habitation organization. As a result, some of the dwellings built by aid agencies were never occupied, or were later abandoned as their styles, configurations, and proximity to livelihoods were not consistent with local socio-economic and cultural norms.

Problematic Case Studies

St. Bernard Parish, New Orleans

Type

Recovery

Post-Katrina, 2005

Location

Coastal Louisiana

USA

“

One of the most important impacts of not being “recognized” by outside helpers was that there were no alternative or even temporary spaces for their large numbers of kin to gather to enact the weekly rituals they had followed for generations

The majority of African Americans from the New Orleans bayou area of St. Bernard Parish returned to their severely damaged home environment after the storm. Like tens of thousands of others, they relocated to the 240 square-foot trailers provided by FEMA. Their very large families had been rooted to the area for generations and comprised dozens and sometimes hundreds of related individuals living in close proximity. But their style of family organization did not fit into FEMA’s recovery template. One of the most important impacts of not being “recognized” by outside helpers was that there were no alternative or even temporary spaces for their large numbers of kin to gather to enact the weekly rituals they had followed for generations-- to share food, stories, and childcare, to circulate essential information and renew bonds of interdependence. The blow to their cultural system left them without access to their interdependent ties and the years they were made to endure these problems led to widespread suffering--physical, mental, and emotional. These consequences also lengthened by years the time it took people to recover.